How to Avoid Wasting Your Weekend Binge-Watching TV

Stoic Advice from a First Century Philosopher

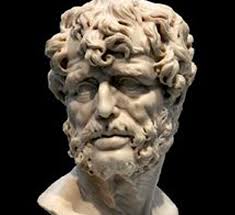

Seneca the Younger lived from around 4 B.C. to 65 A.D.

From the watch on our wrist to the phone in our pockets; from the dashboard in our cars to the walls in our boardrooms and classrooms; from our TVs to our nightstands. Time. It's an indubitable part of our existence, an integral piece of our understanding of our world, an earmark of our daily maneuverings.

Just like our car breaks down, our heels wear-out, our milk spoils, Time expires over...time. Most of us have been a long life to live but how much longer do we really have? Decades? Years?

Why are we so confident in our longevity? It can be given and given and given, and then gone — just like that — without notice, without warning, without expectation.

Now, what if we lived with the mindframe of Memento mori?

In Seneca’s first letter in his Letters from a Stoic, he writes about the nature of time to his friend, Lucilius. He encourages his friend–and us–to “gather and save our time.” Is that possible? Can we gather Time like we would gather flowers from a garden?

Seneca, even in his day, was aware how time can be “forced from us, or filched away, or merely slipped from our hands.” We can all admit how cultural expectations and social influences “force” us to spend our time in certain ways: binge-watching TV shows on weekends, scrolling through news feeds that abounds to hours, listening to nothing but jams on a road-trip.

The question is: What’s the end? What’s the aim? What’s the target?

Seneca continues:

The most disgraceful kind of loss…is due to carelessness. Furthermore, if you will pay close heed to the problem, you will find that the largest portion of our life passses while we are doing ill, a goodly share while we are doing nothing, and the whole while we are doing that which is not the purpose.

I don’t think binge-watching some shows, or flicking-up, flicking-down on social media would be seen by most as so-called “careless.” But a Stoic thinker would ask about the rationale that goes beyond just the activity in and of itself.

“Doing ill” can be interpreted in our time as being unsatisfied, frustrated, joyless, angry, or anxious. We seek to become more satisfied. We find ways to release that frustration. We jump from one-thing-to-another to escape a joyless state. We ruffle our feathers and become consumed in anger. We distract ourselves to assuage any anxiety.

These emotional vicissitudes impinge on our slowly dwindling and hence valuable Time. Are we using It wisely? Is our choice to use our Time actually making us “ill”? We have to own sliding into dissatisfaction, growing into frustration, falling into joylessness, steaming into anger, and fretting to anxiety. And what is the product of these self-imposed circumstances? Nothing but more of it.

We find little purpose and little productiveness to being soaked in dissatisfaction, flurried in frustration, stepped in miserableness, treading water in anger, and frazzled in angst.

Seneca saw each day as not living but “dying daily.” And — as gloomy-and-gray as it is — he’s right. Our skin dies, our mind ages, our entire body breaks-down, our relationship will last less-and-less, and our Time is ticking, ticking, towards zero.

Fearing death, we may reframe the way Seneca does: “the major portion of death has already passed.” With what we do, we are relinquishing our Time. Who’s in possession of our Time? Pleasure or purpose? Loss or love? Life or death?

Seneca implores: “Hold every hour into our grasp.”

It’s progressively challenging — and even counterculture — for us to attend to each hour as it passes. We live on a ceaseless treadmill, a never-ending loop of tasks, commitments, places-to-be and people-to-see. Drive-thrus-over-sit-downs, texting-over-conversation, followers-over-true friends. We settle for what is fast, convenient, and quantitatively larger (and thus qualitatively insignificant).

Many times we “postpone” what’s really important, such as: one-on-one time with family, time to reflect on this past year, making a needed lifestyle change. We get caught-up in the current, diverted by the lights, enraptured by the rhythm. We become reactionary, unpredictable, and shortsighted. And accordingly, “life speeds by.”

Seneca holds that our Time is “entrusted” to us. From this lens, our Time is believed to be sacred, special, salient. If we would subscribe to this philosophy, how much different would we go about things? We wouldn’t procrastinate nor hope nor wish nor un-appreciate nor look-past.

Most of us avoid — painstakingly, hypervigilantly, with dedication — to be in debt: credit card fees, mortgage payments, student loans. We repel having pending financial matters that hang-over-our-heads, that burden us, that linger around every corner. But why don’t we see that the poor decisions that we make so regularly with our Time have us in another type of “debt”? We are “loaned” Time, this “precious commodity,” by the Earth but we're bad stewards of it. If we value ourselves and we value our lives, then we would — logically — value our Time.

We would take it as our duty to use our Time in the best manner (which is determined and decided-upon with prudence, judiciousness, and patience).

Many say that they live their lives to the fullest (and many believe they do). Well, then that would matter is your definition of “the fullest.” This common platitude that men and women, young and old alike regurgitate typically carries-out “the fullest” as the most pleasurable, the most desirable, the most attractive, the most expensive, the most fun. And Seneca would retort of those who standby this: “What fools these mortals be!” Why? — because “The Most” is short-lived, and thus, trivial, insubstantial, and folly.

If Time is money, then many are suffering in poverty. Their “expenditures” expire quickly and last not long. Their choices on what to use their Time on makes them uninformed customers, unwise shoppers, and asinine buyers. They get that and this because he or she did. If you question them on their reason, their thought-process behind their use of Time, they’ll be unprepared and ashen when pressed for an answer.

Nevertheless, soon enough you’ll be approaching “the dregs of the cask,” the remaining crumbs, the last drop, the final pick of your Time. Will you reflect with satisfaction on how you lived your life, or will you look back with regret? We can decide now to live-out each day that we’re given, responsibly. We do this by awareness and appreciation for being alive, for having things and people we love and enjoy. And so, we can really live our lives to the fullest.

breven bell writes for Beautiful Voyager, Invisible Illness, and Thoughts and Ideas on Medium. Follow him on Twitter.